There are two types of depression, we are sometimes told: Depression, and bipolar disorder. To my way of thinking, at least, ALL depressions are bipolar in nature. It’s just that those who don’t have the wild swings of high to low, but just from “normal” to low, aren’t considered to be be bipolar. (The report on Cannabis and suicide doesn’t mention PD, but it seemed close enough to the topic of depression that I included it.

But what do I know? I’m not a trained psychiatrist or psychologist.Here’s some articles from some folks who seem to have expertise in the area:

First: find out whether someone with PD is depressed.

Williams JR, Hirsch ES, Anderson K, Bush AL, Goldstein SR, Grill S, Lehmann S, Little JT, Margolis RL, Palanci J, Pontone G, Weiss H, Rabins P, Marsh L. A comparison of nine scales to detect depression in Parkinson disease: which scale to use? Neurology. 2012 Mar 27;78(13):998-1006. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824d587f. Epub 2012 Mar 14. PMID: 22422897; PMCID: PMC3310315.

Conclusions: The Geriatric Depression scale (GDS-30) may be the most efficient depression screening scale to use in PD because of its brevity, favorable psychometric properties, and lack of copyright protection. However, all scales studied, except for the UPDRS Depression, are valid screening tools when PD-specific cutoff scores are used. (emphasis added).

And guess what? Comorbidities need to be considered, and depression rating scales don’t really tease out one of the more common ones.

Calleo J, Williams JR, Amspoker AB, Swearingen L, Hirsch ES, Anderson K, Goldstein SR, Grill S, Lehmann S, Little JT, Margolis RL, Palanci J, Pontone GM, Weiss H, Rabins P, Marsh L. Application of depression rating scales in patients with Parkinson’s disease with and without co-Occurring anxiety. J Parkinsons Dis. 2013;3(4):603-8. doi: 10.3233/JPD-130264. PMID: 24275604.

Conclusions: Co-occurring anxiety disorders do not impact performance of depression rating scales in depressed PD patients. However, depression rating scales do not adequately identify anxiety disturbances alone or in patients with depression.

Why should we care? Because depression has an adverse effect on daily living for those with PD.

Pontone GM, Bakker CC, Chen S, Mari Z, Marsh L, Rabins PV, Williams JR, Bassett SS. The longitudinal impact of depression on disability in Parkinson disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016 May;31(5):458-65. doi: 10.1002/gps.4350. Epub 2015 Aug 18. PMID: 26284815; PMCID: PMC6445642.

Objective: Depression in Parkinson disease (PD) is a common problem that worsens quality of life and causes disability. However, little is known about the longitudinal impact of depression on disability in PD. This study examined the association between disability and DSM-IV-TR depression status across six years.

Results: A total of 43 participants were depressed at baseline compared to 94 without depression. Depressed participants were more likely to be female, were less educated, were less likely to take dopamine agonists, and more likely to have motor fluctuations. Controlling for these variables, symptomatic depression predicted greater disability compared to both never depressed (p = 0.0133) and remitted depression (p = 0.0009). Disability associated with symptomatic depression at baseline was greater over the entire six-year period compared to participants with remitted depressive episodes or who were never depressed.

Conclusions: Persisting depression is associated with a long-term adverse impact on daily functioning in PD. Adequate treatment or spontaneous remission of depression improves ADL function. (emphasis added).

Teamwork is needed. If the person with PD can’t be their own advocate, then someone needs to help coordinate and communicate.

Taylor J, Anderson WS, Brandt J, Mari Z, Pontone GM. Neuropsychiatric Complications of Parkinson Disease Treatments: Importance of Multidisciplinary Care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016 Dec;24(12):1171-1180. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2016.08.017. Epub 2016 Sep 3. PMID: 27746069; PMCID: PMC5136297.

Abstract

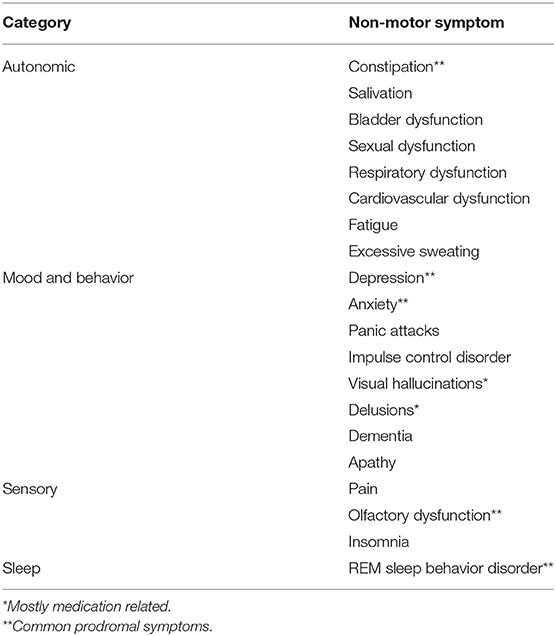

Although Parkinson disease (PD) is defined clinically by its motor symptoms, it is increasingly recognized that much of the disability and worsened quality of life experienced by patients with PD is attributable to psychiatric symptoms. The authors describe a model of multidisciplinary care that enables these symptoms to be effectively managed. They describe neuropsychiatric complications of PD itself and pharmacologic and neurostimulation treatments for parkinsonian motor symptoms and discuss the management of these complications. Specifically, they describe the clinical associations between motor fluctuations and anxiety and depressive symptoms, the compulsive overuse of dopaminergic medications prescribed for motor symptoms (the dopamine dysregulation syndrome), and neuropsychiatric complications of these medications, including impulse control disorders, psychosis, and manic syndromes. Optimal management of these problems requires close collaboration across disciplines because of the potential for interactions among the pathophysiologic process of PD, motor symptoms, dopaminergic drugs, and psychiatric symptoms. The authors emphasize how their model of multidisciplinary care facilitates close collaboration among psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, neurologists, and functional neurosurgeons and how this facilitates effective care for patients who develop the specific neuropsychiatric complications discussed.

And, with a cautionary reminder that correlation does not equal causation, and that the new release about the referenced article comes from the Council on Drug Abuse: (which could possibly have a conflict of interest regarding the results of the data):

B Han, WM Compton, EB Einstein, ND Volkow. Associations of Suicidality Trends With Cannabis Use as a Function of Sex and Depression Status(link is external). JAMA Network Open. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13025 (2021).

An analysis of survey data from more than 280,000 young adults ages 18-35 showed that cannabis (marijuana) use was associated with increased risks of thoughts of suicide (suicidal ideation), suicide plan, and suicide attempt. These associations remained regardless of whether someone was also experiencing depression, and the risks were greater for women than for men. The study published online today in JAMA Network Open and was conducted by researchers at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health.

“While we cannot establish that cannabis use caused the increased suicidality we observed in this study, these associations warrant further research, especially given the great burden of suicide on young adults,” said NIDA Director Nora Volkow, M.D., senior author of this study. “As we better understand the relationship between cannabis use, depression, and suicidality, clinicians will be able to provide better guidance and care to patients.”

On the other hand, it could be that young adults are depressed or suicidal because they live in a world in which constant war is being fought, in which war profiteering is not a crime, in which they see politics reduced not to a game of collaboration and mutual benefit, but a zero sum game in which the winner takes all. Perhaps they are depressed over the failure of the governments to address the mounting scientific evidence that climate “change” is resulting in climate chaos, and yet the governments of the world, funded by the fossil fuel industries, are “rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic” while the media band plays on. I could go on, but I won’t.

I used to be suicidal, but my life has changed.

More to the point:

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is available today, providing suicide prevention and mental health crisis assistance at 1-800-273-8255 and through online chats. 988 is not a nationwide calling code right now. The Veterans Crisis Line is available today, providing Veteran specific suicide prevention and crisis assistance at 1 800 273 8255 (Press 1), by texting 838255, and through online chats at veteranscrisisline.net. On July 16, 2020, the FCC adopted rules to establish 988 as the new, nationwide, easy-to-remember 3-digit phone number for Americans in crisis to connect with suicide prevention and mental health crisis counselors.

And a final note: one of the main defenses against depression is activity is physical activity and human or non-human interaction. So get out here and run a mile, walk along a nature trail, play some music, call a friend, join a group or club, hug a tree, kiss a girl/boy, and get connected with the world we live in.

You’ll feel better if you do.

###