Jerry Coker, who was one of my instructors my first year in undergraduate college, and then again my last semester before graduation , had an hypothesis that for improvisation to be enjoyable, it had to be approximately 75% predictable and 25% unpredictable. Vary too far from those parameters, and you end up with something that is either too boring and predictable, or something that leaves the listener wondering what’s going on, trying to guess where the melody is.

I never advanced far enough to get his insights on swing, or the concept of where the beat is. Duke Ellington, whom I saw at a festival once, did have a short primer on swing. He began with the person who snaps his fingers or taps his feet on the downbeats (ONE-and-TWO-and….). Then he progressed to the folks who tapped their feet or snapped their fingers on the upbeat (1-AND-two-AND..). I forget where it went from there (maybe to Latin rhythm patterns), although I do remember him saying that when he greeted people, he always gave two kisses to the right, and two to the left, one for each cheek.

Love You Madly (ending)

Today’s readings all relate to music and movement –

From Saluja A, Goyal V, Dhamija RK. Multi-Modal Rehabilitation Therapy in Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2023 Jan;26(Suppl 1):S15-S25. doi: 10.4103/aian.aian_164_22. Epub 2022 Nov 21. PMID: 37092020; PMCID: PMC10114534.

(emphasis added to the section quoted below):

Dance, Music, and Singing Therapy in Pd Rehabilitation

Dancing may improve speed of movement, balance, wellbeing, and QOL in patients with PD.[74,75] Multiple dancing interventions and their impact on symptomatology of PD patients have been assessed. In a systematic review of 38 articles that studied the role of various dancing interventions (tango, waltz/foxtrot, Sardinian folk dancing, Irish set dancing, Brazilian samba, Zumba, mixed dance forms, and home-based dance interventions), there was a moderate-to-large beneficial effect of dancing interventions in mild-to-moderate PD. Dancing sessions (once/week to daily for 30 minutes to 2 hours) significantly improved balance, total UPDRS, mobility, endurance, gait freezing, and depression among PD patients.[76]

Music and rhythmic auditory stimulation can improve gait parameters in PD.[77] BEATWALK is a smartphone-based application that initially assesses cadence in PD patients and then progressively increases musical tempo in order to reach the desired speed. A recent study found that BEATWALK significantly improved gait velocity (P < 0.01), cadence (P: 0.01), stride length (P: 0.04), and distance (P: 0.01) among 39 PD patients who could walk unaided and had no gait freezing.[78] The ParkinSong trial studied the effect of singing intervention (at weekly and monthly intervals) in PD and found significant improvements in vocal intensity (P = 0.018), maximum expiratory pressure (P = 0.032), and voice-related QOL (P = 0.043) among PD patients when compared to controls.[79] A recent systematic review and meta-analysis including 67 publications found that tango resulted in significantly improved UPDRS-III scores (Z = 2.87, P = 0.004) and TUG scores (Z = 11.25, P < 0.00001), whereas PD-specific dance resulted in improvement in PDQ-39 scores (Z = 3.77, P = 0.0002) when compared to usual care.[80]

Cox L, Youmans-Jones J. Dance Is a Healing Art. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2023 Apr 10:1-12. doi: 10.1007/s40521-023-00332-x. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37361639; PMCID: PMC10088655.

This article is considered an Opinion Statement rather than a “research study,”although they used the same armchair/desk jockey methods used by many reviews and meta-reviews. From the abstract (emphasis added):

The purpose of this review is to evaluate the health benefits of dance and dance therapy in various health domains. Dance interventions included movement therapy with certified therapists, common dances such as ballroom dancing, salsa, and cha-cha as well as ethnic dances, such as the Chinese Guozhuang Dance and the Native American jingle dance. The health domains included depression, cognitive function, neuromotor function, dementia, balance, neurological growth factors, and subjective well-being. The National Library of Medicine, Congress of Library, and the Internet were searched using the terms: dance, dance movement therapy, health, cognitive function, healing, neurological function, neuromotor function, and affective disorders from 1831 to January 2, 2023. Two-thousand five hundred and ninety-one articles were identified. Articles were selected if they provided information on the health benefits of dance in one or more of the above domains as compared to a “non-dance” control population. Studies included systematic reviews, randomized controlled studies, and long-term perspective studies. Most of the subjects in the studies were considered “elderly,” which was generally defined as 65 years or older. However, the benefits of DI on executive function were also demonstrated in primary school children. Overall, the studies demonstrated that DI provided benefits in several physical and psychological parameters as well as executive function as compared with regular exercise alone. Impressive findings were that dance was associated with increased brain volume and function and neurotrophic growth function. The populations studied included subjects who were “healthy” older adults and children who had dementia, cognitive dysfunction, Parkinson’s disease, or depression.

The benefits of dance for PwPs include movements and connections with others:

Jola C, Sundström M, McLeod J. Benefits of dance for Parkinson’s: The music, the moves, and the company. PLoS One. 2022 Nov 21;17(11):e0265921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0265921. PMID: 36409733; PMCID: PMC9678293.

From the abstract:

Dance classes designed for people with Parkinson’s are very popular and associated not only with increasing individuals’ motor control abilities but also their mood; not least by providing a social network and the enjoyment of the music. However, quantitative evidence of the benefits is inconsistent and often lacks in power. For a better understanding of the contradictory findings between participants’ felt experiences and existing quantitative findings in response to dance classes, we employed a mixed method approach that focussed on the effects of music. Participant experience of the dance class was explored by means of semi-structured interviews and gait changes were measured in a within-subjects design through the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test before and after class, with and without music. We chose the TUG test for its ecological validity, as it is a simple test that resembles movements done in class. We hypothesised that the music and the dance class would have a facilitating effect on the TUG performance. In line with existing research, we found that before class, the gait of 26 participants was significantly improved when accompanied by a soundtrack. However, after class, music did not have a significantly facilitating effect, yet gait without music significantly improved after class compared to before.We suggest that whilst the music acts as an external stimulator for movement before the dance class, after the dance class, participants have an internalised music or rhythm that supports their motor control. Thus, externally played music is of less relevance. The importance of music was further emphasised in the qualitative data alongside social themes. A better understanding of how music and dance affects Parkinson’s symptoms and what aspects make individuals ‘feel better’ will help in the design of future interventions.

The entire article is Open Access at the link above. My own impression of the discussion of the contradictory results (from what was expected) reminded me of a quote my statistics professor was fond of repeating: It is meaningless to discuss what the data might have been if the data were something other than what they are.

As a PwP, one explanation for the lack of significance difference in the TUG post-test could very well be fatigue. I, therefore, suggest that this could be looked into as a possible explanation for the lack of significant difference between external music v no external music stimulus. Clearly, “Further research is needed.”

Morris ME, McConvey V, Wittwer JE, Slade SC, Blackberry I, Hackney ME, Haines S, Brown L, Collin E. Dancing for Parkinson’s Disease Online: Clinical Trial Process Evaluation. Healthcare (Basel). 2023 Feb 17;11(4):604. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11040604. PMID: 36833138; PMCID: PMC9957486.

The above citation reports on a clinical trial which was conducted with a fairly large and coordinated collaborative effort. Again, an excerpt from the abstract:

Results: Twelve people with PD, four dance instructors and two physiotherapists, participated in a 6-week online dance program. There was no attrition, nor were there any adverse events. Program fidelity was strong with few protocol variations. Classes were delivered as planned, with 100% attendance. Dancers valued skills mastery. Dance teachers found digital delivery to be engaging and practical. The safety of online testing was facilitated by careful screening and a home safety checklist. Conclusions: It is feasible to deliver online dancing to people with early PD.

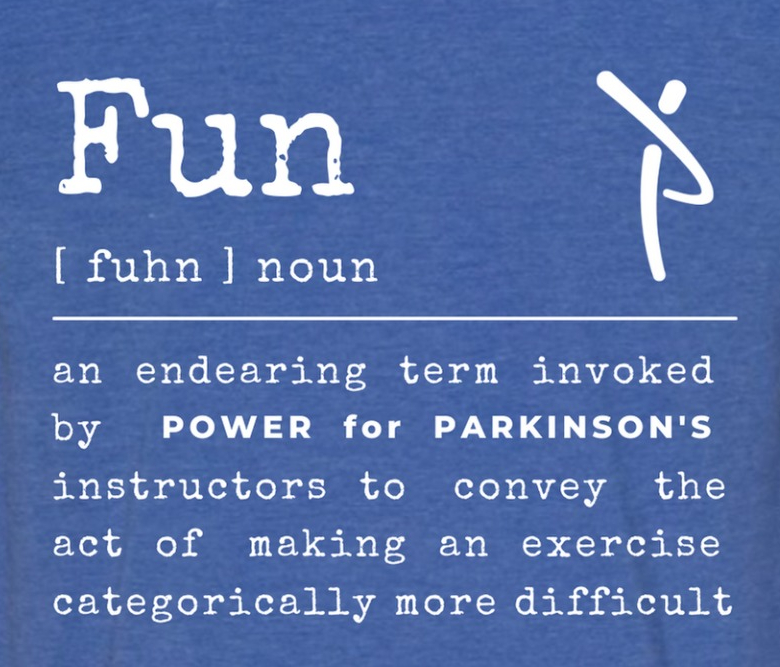

As a PwP who has participated in Power for Parkinson’s online video dance Rhythm and Moves and other exercise videos, both live and asynchronously, the last line comes as no surprise.

The hour grows late, and I have medications to take before I sleep, oh so many medications to take before I sleep. To sleep, perchance to dream…

###