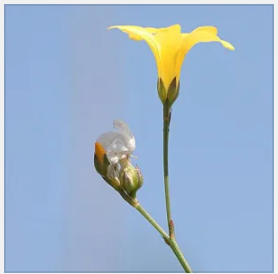

Clematis texensis – Scarlet Leatherflower

I just realized that there is an analogy between the pandemic coronavirus now causing troubles throughout the planet’s human organizations and the title and subtitle of this blog – “Return To The Natives – Native Plants Are The Answer.”

C. texensis is endemic to the Texas Hill Country, or the Edwards Plateau, although because of the scarlet flowers, it has been exported to other locations for cultivation. However, it doesn’t seem to be an aggressive plant, so most places outside of Texas where it is found are probably in containers, where they are tended carefully by loving horticulturists.

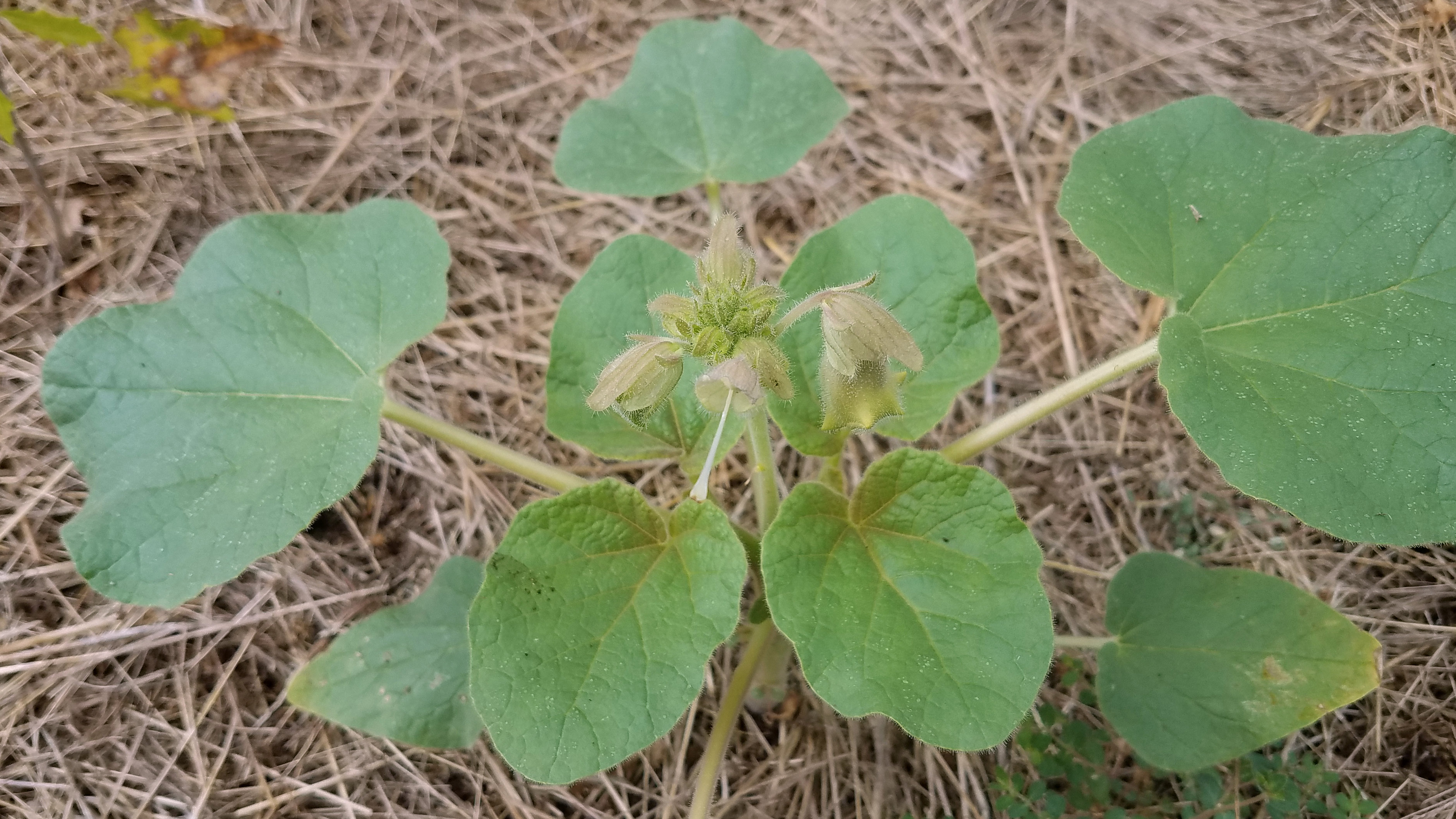

The example shown above is a next door neighbor example of this phenomenon: Although it it is in Williamson County, TX, it was introduced and is under cultivation. I don’t know of any locations where it is growing in Williamson County without having been introduced by humans. But – it is native to Texas, and to neighboring counties, and who knows? – there might be some undiscovered instances of this species in the Balcones Canyon National Wildlife Refuge.

Unlike some other plants, like Poison Ivy, Malta Star Thistle, Perennial Rye, and Bur Clover, which are aggressive and spread rapidly when they are introduced to an area through human intervention, often by poor mowing practices, this one is unlikely to dominate your garden. But with the right conditions and in the right place, it can and will flourish in Central Texas.

More detailed information on Clematis texensis can be found at Studies on the Vascular Plants of Williamson County, Texas. If that is too much detail for you, there’s always the Native Plant Information Network (NPIN) database at the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center

The analogy mentioned above?

The pandemic virus is like an exotic plant that is introduced to areas where it doesn’t belong – and spreads, unchecked, unless we take quick action to recognize the problem and isolate, treat, and follow up on contacts, to eradicate and mitigate the adverse effects. The same analogy applies to invasive animals, whether Zebra mussels in the lakes of the South, or pythons in the Florida Everglades. It’s hard to get the genie back in the bottle, or to get everything back inside Pandora’s box.

Stay home. Practice good hygiene, whether traveling or working with plants. The only thing that can prevent pandemics is you, to borrow a slogan from a well known fire prevention campaign.

Plant and grow things that are native to the area in which you live – practice proper hygiene when traveling from place to place, being careful not to spread seeds through carelessness, and if you gotta mow, mow only at the right time and the right places that need mowing for the primary reason of safety. Bermuda grass is hard to eradicate once it has spread, and viruses are hard to kill but easily spread through careless hygiene practices.

Don’t “stop to smell the roses” – Learn about the plants that are native to your area, and take the time to enjoy them and their relationships with the wildlife, butterflies, and native bees that are in your six feet of separation.

###