It’s been said that if you’ve met one person with Parkinson’s Disease (PD), then you’ve met one person with PD. This week I met another person with PD, who said the same thing. The implication is that PD is different for everyone who has it (or any other form of parkinsonism, as the terminology goes). As stated by one of the contributing authors:

The truth is that every person living with PD has a unique expression of the dysfunction and precise balance of factors contributing to this idiosyncratic disease journey.

Today, we look at and try to communicate in “normal” language the following open access article. To read the original, just click on the link at the bottom of this post.

Different pieces of the same puzzle: a multifaceted perspective on the complex biological basis of Parkinson’s disease.

As noted in the abstract:

Notably, … growing recognition that the definition of PD as a single disease should be reconsidered, perhaps each with its own unique pathobiology and treatment regimen.

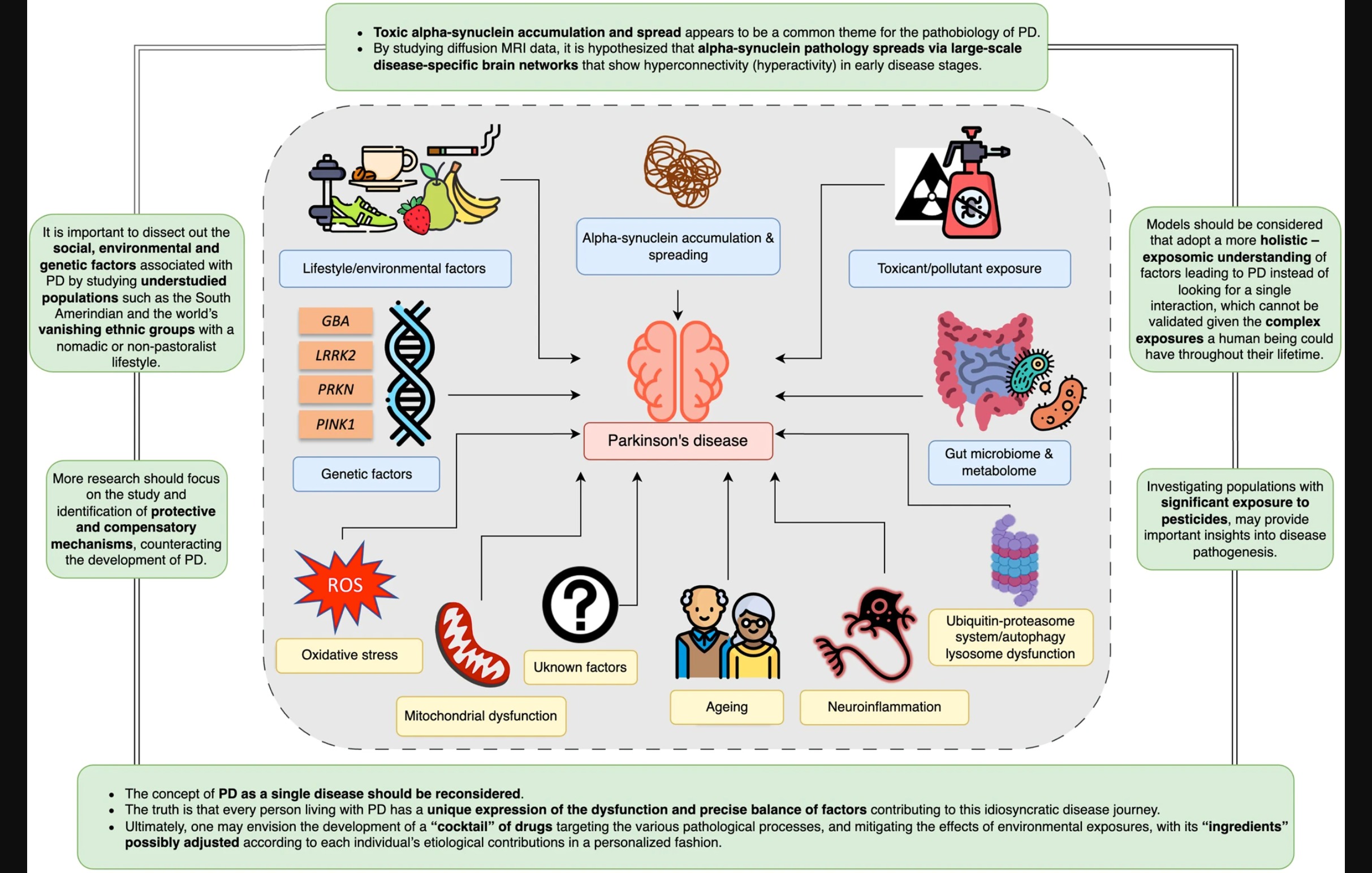

Figure 1: Illustration from the article

Gene Genie

Pathological variations in a couple of different genes or enzymes ( PRKN, PINK1) are the strongest predictors of the disease. On the other hand, variations in other specific genes or enzymes (such as GBA and LRRK2) greatly increase an individual’s risk, and current research studies are looking into trying to tease out environmental factors, lifestyle behaviors or changes that might modify the course or severity of PD.

Down at the cellular level of our bodies, two other pathologies impact the progression of this neurodegenerative disease. One is the aggregation of alpha-synuclein proteins, the other is mitochondrial dysfunction, where the alpha-synuclein proteins fail to get cleared out and eventually result in apoptosis, or cell death. Part of this may be due to the aging process, but the occurrence of early onset PD should make us wary of the simplistic notion that PD symptoms are “just a sign of getting older.” The aggregation of alpha-synuclein proteins may be due to various reasons, such as over-production, while the end result is the same: mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to increased neurodegeneration.

LRRK2-ing around

Since its discovery in the early 2000s, the LRRK2 gene and leucine rich repeat kinase 2 enzyme have been repeatedly associated with the risk for PD.

Despite the fact that there have been no formal epidemiologic studies, and figures cited in the literature are mostly from clinical reports, LRRK2 dysfunctional mutations appear to confer the highest risk of PD. LRRK2 coding substitutions tend to be population specific: Basques, North African Berbers, Ashkenazi Jews, and South Eastern Asia. Why these mutations (or variations) seem to provide an evolutionary advantage, allowing them to be passed on to future generations, is unknown.

Since PD is a multifactorial disease, the article proposes that animal models of the disease should also include factors such as genetic variations, environmental toxins, neurons, and the immune system, in order to find out where the biological intersections are.

Toxin exposure

Genetic risk factors, along with other factors, including toxins (including pesticides), are believed to have a cumulative impact on the brain, resulting in alpha-synuclein protein accumulation, low-grade inflammation, and the eventual apoptosis of dopaminergic neurons. These hypotheses are based on research data from high income countries. Two Sub Saharan African tribes, which have a nomadic or partly nomadic lifestyle, have virtually no exposure to pesticides, and no reported cases of parkinsonism. The author of this section suggests that “absence of” studies might be as important as “presence of” studies, in the search for causes of PD.

The genetic predisposition for PD may account for only 1/3 of the risk for PD.

…there is strong evidence to implicate pesticides as a significant environmental factor associated with the disease, especially paraquat, rotenone, and organochlorines.

Although scientific research has shown its risks, paraquat is still widely used (and has not banned in the USA, although book bans seem to be popular. I have yet to hear of a book that caused PD). Loose regulation of pesticides in Latin America seems highly correlated with the occurrence of PD compared to other countries,where paraquat is either restricted or banned. Studies comparing PD in populations where paraquat is restricted or banned vs. those in which its use is more loosely regulated, including longitudinal studies from conception to end of life, are suggested. Finding biomarkers of chronic or long term exposure to such pesticides which might help predict risk of PD could be one goal of such studies.

Toxic Hoarders: Accumulation of alpha-synuclein

Misfolded alpha-synuclein is the primary constituent of Lewy bodies, as was discovered over two decades ago. Further, variants in the alpha-synuclein gene (SNCA) were found to cause familial PD, linking genetics to PD for the first time. Since then, research has shown that it can also cause neurodegeneration and leads to apoptosis of mitochondria, and then on to the death of dopaminergic cells.

It is thought that abnormal alpha-synuclein s generated in the intestinal tract, where it causes inflammation and then can spread to the brain through the vagus nerve or other pathways.

Recent research has found the CHCHD2 gene as a cause for hereditary PD. This gene is localized to mitochondria, and animal model studies have show an increase in alpha synuclein in the brain. Whether alpha-synuclein damages mitochondria or mitochondrial dysfunction results in accumulation of misfolded alpha-synuclein is yet to be figured out.

Whether PD is body-first or brain-first in terms of pathogenesis is no longer a tenable position. Over the last 15 years, it has been recognized that “PD” should refer to “Parkinson’s Diseases,” which include a variety of factors, including genetic, pesticides exposures, pollutants, exercise, diet, viral infection, head trauma, and inflammatory diseases, all of which interact to affect the progression of the symptoms.

Complexity, multiplicity and interactivity

Until recently, much of PD research has assumed that PD is a single disease; more recently, it has been accepted by many as a systemic disease with multiple effects on various systems instead of a localized neurological disorder.

One of the authors of this article proposes a “threshold model” in which the different triggers work independently or simultaneously to build up stress on the various systems until reaching a a damage threshold, after which the initial stage(s) of the disease are developed.

We understand now that the disease initiation process is not following a single model. So, in one case, a pathogenic gene variant could interact with different environmental factors causing the disease (gene-environment interaction). In another case, different genetic variants could interact to cause the disease (gene–gene interaction), or different pollutants can interact to lead to the disease (environment-environment interaction). This can be even extended to involve more factors e.g., social stressors, metabolic diseases, etc. This model could allow us to adopt a more holistic – exposure over lifetime understanding of factors leading to PD instead of looking for a single interaction, which cannot be validated given the complex exposures a human being could have throughout their lifetime.

On the other hand, given that there is evidence that implicates both genetic and environmental factors in the occurrence and progression of PD, there are commonalities:

- PD is progressive and degenerative.

- PD includes the change of “normal” processes past a tipping point, to spiral downward into cellular degeneration. This includes factors such as inflammation, abnormal protein aggregation, and metabolic imbalance. Where it begins and the individual’s initial cause may well differ from person to person.

- The disease(s) are triggered many years before symptoms of Parkinsonism become obvious.

Another contributor to this article emphasized protective and preventive factors such as

anti-inflammatory agents, antioxidants, calcium channel agonists, inhibitors of alpha-synuclein aggregation, neurotrophic factors and protective lifestyle factors, such as coffee drinking.“

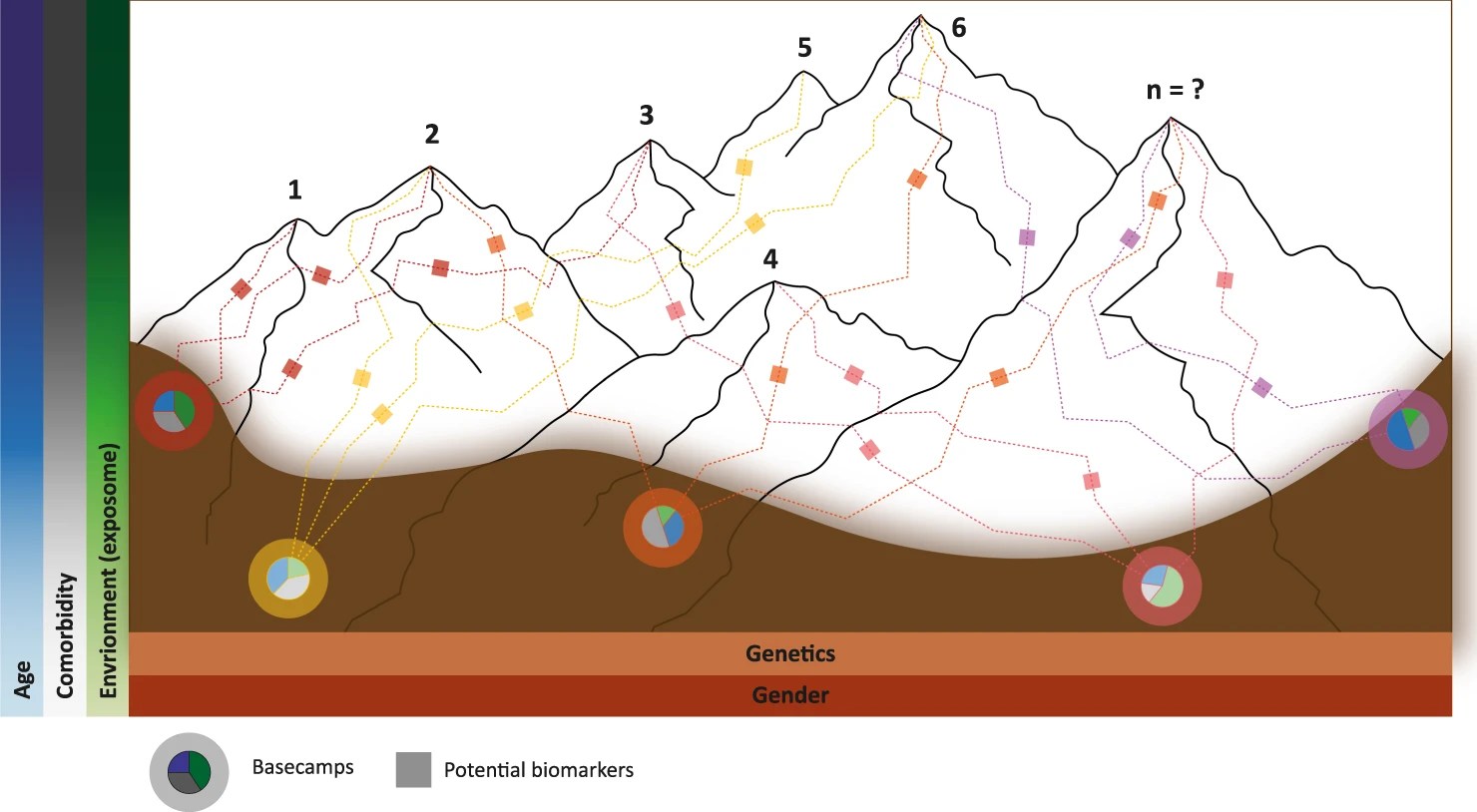

Reference is made to a Mountain Range model for PD, in which the genetic risk is considered as different “basecamps” at the valley at the foot of the mountain range, and the various risk factors or protective factors interact with the genetic risk to impact onset age, rapidity of progression, etc. Pie Charts at the basecamps indicate these risks and protective factors, and boxes along the paths or trails represent potential biomarkers. The height of the mountains within the range represent how rapidly the disease progresses.

Figure 2. The Mountain Range model. (This figure is from Farrow, S.L., Cooper, A.A. & O’Sullivan, J.M. Redefining the hypotheses driving Parkinson’s diseases research. npj Parkinsons Dis. 8, 45 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41531-022-00307-w, which is an open access article ).

The microbiome-gut-brain-axis

It has been suggested that the disease originates in the gut biome, while theopposite theory that it originates in the brain and spreads to the gut microbiome also has support. It appears that it is possible that both explanations may be true, depending on the individual. As noted at the beginning, each case of Parkinson’s is different, to a certain extent Recent studies have indicated that once the process has begun, it may spread bi-directionally.

Loss of bacteria producing neuroprotective molecules such as short-chain fatty acids (a lack of which are linked to constipation, gut barrier dysfunction and inflammation, early symptoms related to PD). Corroborating these human observations, animal models suggest that gut microbiome can contribute to PD onset. Definitive proof that they are causative will require large-scale longitudinal studies with multiple samples to determine the role of gut microbial changes in PD. Studies that factor in caffeine intake, cigarette smoking, pesticides and other toxins that affect PD risk impact the gut microbiome are also needed.

In the future, a better understanding of modifiable factors and events operating along the microbiome-gut-brain axis may open up new ways to prevent or change the course of PD.

combo: socio-bio-enviro factors

In 2017, the economic burden of PD only in the USA was $51.9 billion USD. (And that was before COVID and subsequent inflation).

Chile over the last 10 years, epidemiological and demographic data has been used to generate a publicly accessible resource: a nationwide de-identified individual-level electronic health record database. In addition, medical research can access clinical statistics from the Ministry of Health through the Department of Health Statistics and Information (DHSI) and to environmental factor exposure data (i.e., registry of contaminants by geographic districts) through the Ministry of Environment and others. A population of more than 37,000 PD cases over the last 20 years have been identified, mainly in overpopulated or industrialized regions. This shows how environmental factors (pesticides, pollution) influence the pathology of PD. Regional disease prevalence, progression, comorbidities, mortality, social factors, and economic burden can be inferred from the data involved in PD progression. Together, the social, biological, and environmental factors may help to explain why every person with PD has, for the most part, a unique experience and journey.

In conclusion:

Over 200 years after James Parkinson wrote his essay on The Shaking Palsy, we still do not have an answer to the question: What causes Parkinson’s Disease(s)? We can assume with confidence that the cause(s) of the disorder are multifactorial. Because individuals differ in genetics, environment and lifestyle, PD is different for and in each person with PD.

###

Note: The source materials for this blog post were published as Open Access under a Creative Commons license, which can be found at the links above and below. This writer has modified and paraphrased much of the wording from the original article, hopefully to make it more accessible to folks with PD but neither an M.D. or PhD. after their name. Any misinterpretation of the original article is solely due to my own shortcomings (I blame it on the Parkinson’s©). I omitted the concluding statement that suggested that since all the contributing authors were either M.D.s or Phd.s, or both, that there might be some biases in their viewpoints. I did notice that lifestyle was listed as a possible factor, but that exercise and dance were not specifically called out.

For anyone who wants to read the entire article, here’s the citation and link.

###