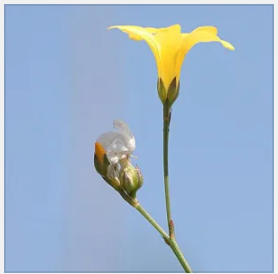

On Tuesday, May 26, 2020, I was participating in an online Parkinson’s exercise class when I heard the sound of engines and saw a mower going across the berm next to a green belt. The first three pictures below show the wildflowers that I had managed to give some room by pulling about 10 bags of invasive grasses and noxious weed from around them since February. The last three pictures show the result of the mowers’ work, having cut the berm bare, including the stands of blooming wildflowers. Warning: disturbing and graphic photographs are included.

I quickly called Ecosystems Landscaping of Austin, the name of the company on the mower’s tee-shirt, who had simply waved at me and turned his mower in the opposite direction when I tried to flag him down. (Granted, I did not have a face mask on. Perhaps he was following COVID-19 prevention precautions).

I spoke on the phone with a Mr. Robert G., who basically let me vent while his company’s employees cut down all the wildflowers still standing on the berm, many of which were not yet in full bloom or had even gone to seed.

He told me that their contracts required them to mow within a certain date. I asked why there weren’t clause(s) that prohibited mowing under unsuitable conditions, such as following rains (we had received at least two inches of rain in the last three days, and the ground was still wet, as was the grass). He claimed that their mower blades were pressure washed before bringing the mowers to the site, and that the blades were set at least three inches high. (I advised him that the Texas DOT guidelines for roadside vegetation management recommend setting the blades at 7 inches for rural areas, and to avoid mowing next to natural preserve areas, which the greenbelt is). I suggested that the Lolium perenne (annual rye grass) and Centaurea melitensis (Malta star thistle), both highly invasive plants, could not have come in during the last two years in as great of numbers as they had without having been carried in on mower blades.

Although the following references are to the Texas Department of Transportation’s (TXDOT) online manual for roadside vegetation management, (click on the “Home” icon to view a PDF version) I remember learning that the first documented case of child abuse in the US was reported to the Animal Welfare Agency and was prosecuted under the laws regarding cruelty to animals. I think any claim that HOAs and other entities are not subject to the same guidelines are spurious by analogy. At best, such an argument is specious.

In short, I observed the following presumed violations of The Texas Department of Transportation guidelines to Roadway and Roadside Maintenance, to name a few:

- Assumed violation of guideline on Invasive Species (Ch.1, Section 3) “which calls for pressure washing of mowing equipment before the equipment enters or leaves designated areas.” as outlined in Special Provision 730-003 (dated 2004) on Roadside mowing which requires notification of the engineer prior to the pressure washing of mowing equipment in order to ensure that plant materials are contained. (An assumption based on the resulting infestation of invasive exotic vegetation. I am willing to retract this assumption if anyone can provide proof of actual pressure washing before moving the mowers into the area. Video with a date stamp would be sufficient and easy to create with a smartphone). (Emphasis added).

- Presumed violation of Section 4: Special Situations, which states “frequent mowing of of native grasses would allow noxious weeds to invade. … “should be cut no lower than seven inches to ensure survivability.” {emphasis added).

- Presumed violation of Section 2: Preserving and Enhancing Habitat: “Diversity – both in plant variety and growth structure – is the key to preserving and enhancing wildlife habitat. … focus on encouraging a diverse native plant population that will provide abundant food and cover for a variety of wildlife.”

- Obvious violation of Chapter 1 Section 3 – levels of management: ” Large stands of wildflowers including fall blooming nectar plants for pollinators should be avoided when mowing unless safety concerns arise.” (emphasis added).

I could go on.

But I am an elderly person with Parkinson’s Disease. I can’t go out waving my machete at the mowers to get them not to mow over stands of blooming wildflowers. I had thought about putting out signs saying “Wildflower Restoration In Progress – Do Not Mow” the day before, but I had other promises to keep. Maybe this Fall. At least I pulled the 10 bags of invasive plants in the last three months. There will be that many fewer invasive plant seeds, and perhaps the native grasses and wildflowers will have a better chance next year.

###